The Dissection of Humanity

- Maria Christodoulou

- Jun 21, 2023

- 5 min read

Content warning: Graphic description of human anatomy dissection by medical students.

“Before you can hear, much less follow, the voice of your soul, you have to win back your body. You have to go on a pilgrimage beneath the skin.”

~ Meggan Watterson, Reveal ~

Lamprocapnos Spectabilis, "Bleeding Heart"

I’m 19 years old. It’s January 1986. The beginning of my second year at Stellenbosch University’s Faculty of Medicine. I’m in the anatomy dissection hall on the fourth floor of the Fisan building for the very first time. My colleagues and I have been assigned to the second table from the end. Christodoulou, Conradie, Conradie, and Conradie. I’m the odd one out - again.

Almost 40 years later, I still remember everything as if it were yesterday. It was the day I met Gertrude. The beginning of my very first pilgrimage beneath the skin.

Rows of stainless-steel tables and harsh fluorescent lights. Vinyl tiles on the floor. Green chalkboards with cherry-coloured wood frames on the walls. Trays of sharp instruments. Black, council issue refuse bins at the end of each table, and a group of fidgety medical students dressed in new and heavily starched white coats. I have a red dress on underneath mine. My roommate, Karen, and I took photographs to mark the occasion.

Professor Malan introduces himself and talks about respect. Reminds us that we are ethically obliged to behave like professionals. Invites us to bow our heads as a Dutch Reformed priest leads us in a prayer to honour the contribution of those we’re about to meet. The smell of formalin and anticipation is in the air.

Finally, the time comes to take out our textbooks and begin. We unwrap the plastic bag and expose her. Our cadaver. A woman. Brown skinned, wrinkled, lifeless and embalmed. I’m afraid to touch her. She looks like she has lived a hard life. Her hair is curly, coarse and sparse. It’s also grey. Even her pubic hair is grey. I haven’t ever thought about greying pubic hair before. Her breasts are shrivelled. Her belly scarred. We name her Gertrude. It seems only fitting she should have a name if we’re going to be intimate.

Johan and I appropriate her right side. Petra and Suzanne her left. We’ll meet in the middle and share discoveries along the way. Johan asks if he can make the first cut and I’m amazed (and appalled) at his eagerness to start. Am I the only one that’s freaked out by this? The only one that doesn’t really want to do it? Everyone around me looks so confident that I don’t dare ask.

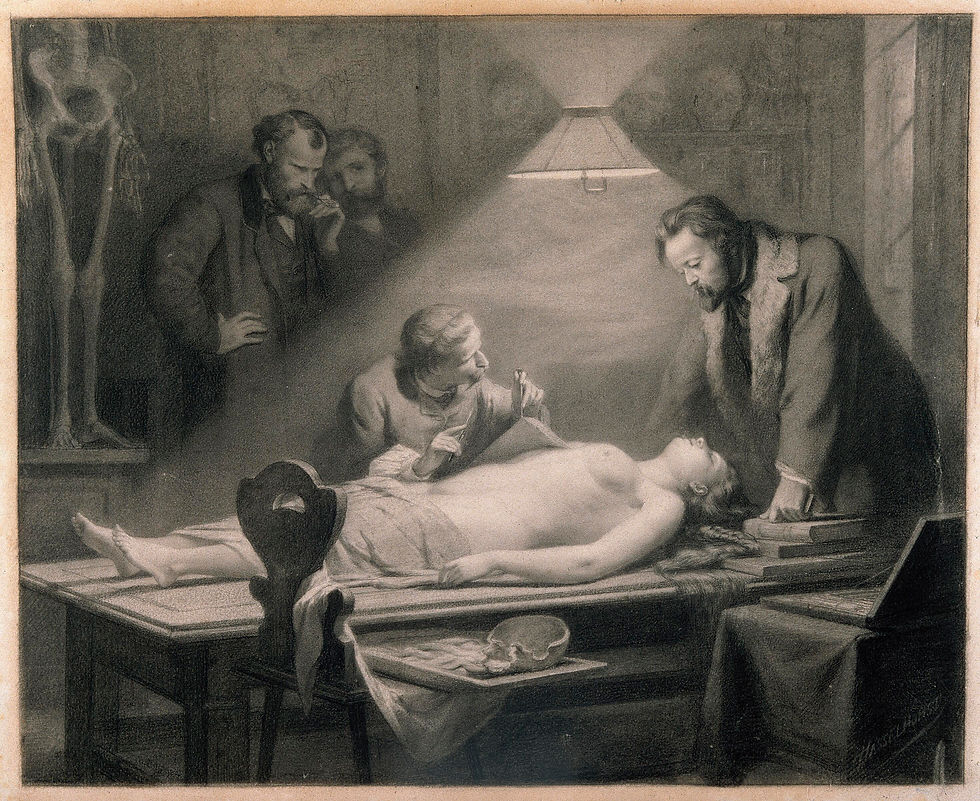

The dissection of a young, beautiful woman directed by J. Ch. G. Lucae (1814-1885) in order to determine the ideal female proportions. Chalk drawing by J. H. Hasselhorst, 1864.

Instead, I watch calmly as Johan slices down the middle of Gertrude’s breastbone with a steady hand. It looks easier than I thought it would and there isn’t any blood, which, in some weird way, I find comforting. Eventually, I feel an unspoken pressure to prove that I have what it takes, so I take a turn. I’m surprised at the sharpness of the blade and how smoothly it slices through her skin. Skin that feels like leather that’s been left out in the sun too long. Tough, dry, brittle. We dissect it loose from the layer of soft, yellow, oily fat that lies beneath it. My stomach turns.

Her muscle fibres look like the frayed edges of dried biltong that’s been torn into strips. We lift a section of them off her ribs and create a flap. An opening. The sound of her bones breaking is sharp and crisp. Her ribcage unlocks and her heart is exposed. I’m surprised at how small it is. No bigger than my fist and compressed between her left lung and a hugely swollen liver. A liver that has overwhelmed her chest cavity and cornered her right lung. I imagine her alone, homeless, with a cigarette dangling from her lips and a bottle of alcohol in her hand.

We remove and inspect her organs one by one. We saw through her skull with an electric blade that sounds like a dentist’s drill and sends bone dust flying into the atmosphere. We slice her brain into segments. We trace and follow her major arteries and veins, and dissect and separate her muscle fibres to their origins and insertions. It takes time this dissection of humanity. An entire year in our case. There’s a lot of human waste in our quest for medical knowledge.

Eventually, it gets easier. We settle into a routine: supervised dissection two afternoons a week and many informal hours at Gertrude’s side in between, especially close to tests and exams. I read the instructions and look over Johan’s shoulder as he dissects - an arrangement that suits us both. We eat lunch with Gertrude, laugh by her side, discuss everyday concerns, behave as though all this is normal, which I guess it is for medical students. I try not to think about what we’re actually doing, but the smell of death embalmed clings to everything – my clothes, my hair, my skin – and follows me everywhere. It’s how everyone on campus identifies me as a second-year medical student. A symbol of my lowly status in the medical hierarchy.

As we systematically reduce Gertrude to a collection of separate body parts, I find myself less interested in her anatomy than I am curious about her story. I want to know who she is. Who she was. What her life was like. How she ended up on a dissection table. There are clues, of course. Her blackened lungs, her swollen liver, her emaciated body. The scars of pregnancy and childbirth. The fact that her brown body was donated to science in an apartheid South Africa. That in itself a story that needs to be told.

As I look back on my years at medical school today, there are many rites and rituals that stand out in my memory. The story of Gertrude is the one most symbolic of my experience of medical education as a whole.

I was - and often still am - the odd one out. An outlier in my way of thinking and being, and a cultural misfit. The process of learning was disembodied, frustrating and depressing. It focused on inanimate organs and body parts rather than human beings. It was about disease instead of health. It reinforced and perpetuated the social injustices of the political context in which it was being taught.

I didn’t realise it back then, but Gertrude not only opened a door for me to learn the anatomy of the human body. She also confronted me with the inescapable reality of the emotional, social and spiritual suffering inflicted on her by the world we both lived in. A world whose impact was indelibly etched onto her body and beginning to seep into mine.

Intuitively, I knew that what I was learning at medical school didn’t even begin to scratch the surface of what was needed for healing to occur. My time with Gertrude, however, planted a seed. A seed that would germinate and sprout many years later and take me on another pilgrimage beneath the skin. A pilgrimage to win back my own body and express the voice of my own soul. A pilgrimage that is unfolding even as I write.

Dr Maria Christodoulou

So incredibly written dear Maria.

I can't even find words to say what I am feeling so I am hugging your heart and thankful that the seed germinated to make you the astounding human you are. Grateful for you! Lara

Beautiful!

This is a book that must be published. You are no outlier to me having met you. You are a fearless pioneer into unchartered territory. You are prepared to challenge current theories which unveil themselves often as less than wisdom. You don't work to systems, imposed, questionable protocols and suspect links to the DSM V. You have deep seated intuition which compounds easily with your training, even if you turn at right angles to new perspectives. I shall be watching your unique entry into an equally unique niche you have chosen for healing. Congr

What an unusual response to learning dissection and anatomy - your wish to know and understand who Gertrude was is testimony to your deep humanity. So moving Maria, x Lynette

Thank you for sharing this.... it touched me... and thank you for honoring Getrude.